The Jacquard Loom Riots

Joseph Marie Jacquard painted by Francois Lepagne.

Joseph-Marie Jacquard was a French weaver and inventor who lived from 1752 to 1834. He was born in Lyon, France, which was known for its silk industry at the time and began his career as a weaver, but he soon became interested in the problem of how to automate the process of weaving complex patterns.

At the time, weaving was a slow and labor-intensive process. Weavers had to manually control the movements of the different colored yarns on the loom to create intricate patterns. This made the production of high-quality textiles both time-consuming and expensive.

The silk industry was a major source of income for the city of Lyon in France. It employed over 30,000 people and made up 25% of the city's exports by 1831. The weavers in Lyon had developed a strong culture and community around their trade, with a guild system that controlled production and prices.

Known as the canuts, the weavers had a lot of power and influence on the industry, controlling the quality of silk production and setting prices for finished products. They worked in small workshops in La Croix-Rousse neighborhood of Lyon, and according to historian Lynn Hunt, the canuts were among the most radical elements of the working class in France at the time. They were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment and the egalitarian spirit of the Revolution. As a result, they were eager to challenge the existing power structures and demand greater political and economic rights.

La Croix-Rousse, Lyon, France

In fact, during the French Revolution, the canuts played an active role in the armed resistance against the counter-revolutionary forces that sought to maintain the old feudal system.

While Jacquard was a weaver, he wasn’t a canut or involved in politics. In fact, he wasn’t particularly well known as a weaver. Instead he decided to spend his time tinkeing to solve the problem of slow production by inventing a loom that could automatically weave complex patterns.

According to the Jacquard Museum in Lyon, Jacquard worked on his invention for over 10 years before finally unveiling the prototype in 1801 and there were many iterations before the patent in 1804. His invention, which he called the Jacquard loom, used a series of punched cards to control the movement of the yarns on the loom.

The punch cards, which were made of heavy paper, were perforated with a series of holes. Each hole corresponded to a specific yarn on the loom, and the position of the holes determined how the yarns would move. By changing the arrangement of the holes on the cards, weavers could create a wide variety of intricate patterns.

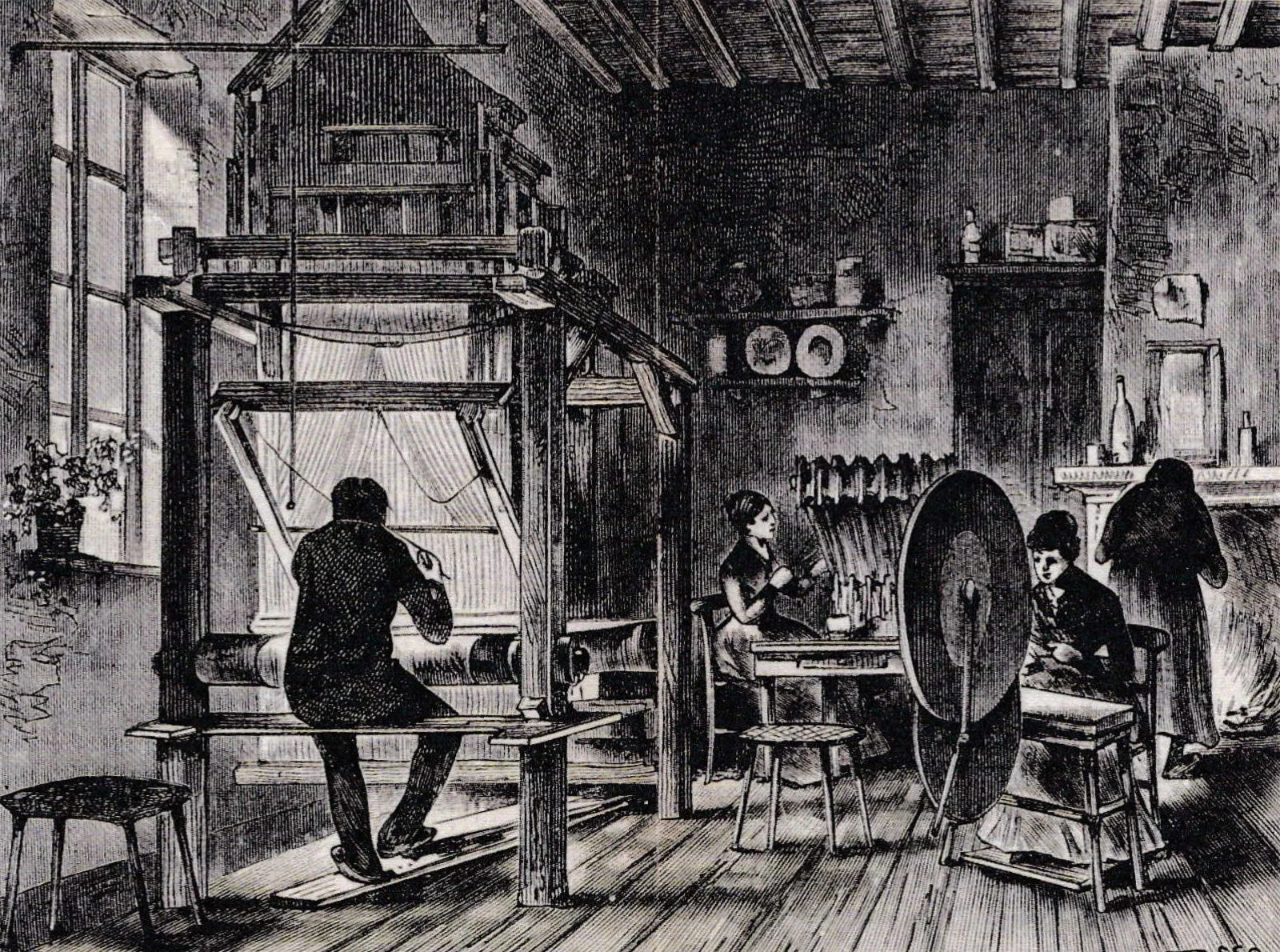

Silk drawloom with jacquard attachment on top. Note the punch cards. This loom is in the La Maison des Canuts in Lyon.

According to the book "Jacquard's Web: How a Hand-Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age" by James Essinger, "News of the new invention soon spread throughout the city, and when Jacquard demonstrated it in public for the first time, the response was mixed. Some weavers were hostile, believing that the new loom would render their traditional skills obsolete, while others were amazed by its versatility and saw the potential for producing more intricate and sophisticated designs than had ever been possible before."

When Jacquard acquired a patent for his loom, it began to spread throughout factories in Lyon and Europe, increasing .

However, the canuts were unhappy with being displaced by machines. They were paid paid a minimum wage, or tariff, and the tariff wasn’t enough to live on, especially with the price of silk going down because of automation.

According to historian James H. Billington, "The new machinery created an ever-widening gulf between the industrialist who owned it and the skilled workers who had previously enjoyed a certain independence within the guild system."

Canut’s would have their workshop set up in their homes in the La Croix-Rousse neighborhood.

This led to what is known as the Canut Revolts. When a settled minimum price for silk was promised and then later was rejected at the last minute by the factory owners, the canuts organized to protest and they soon turned into full-scale riots.

The riots began on November 21, 1831, when a group of silk weavers gathered at the Place des Terreaux. The weavers were joined by other workers, including dyers and tailors, and their numbers swelled to over 30,000 within a few days.

According to historian George Rude, "the protesters marched through the streets, tearing down barricades, fighting with the police and burning factories" (Rude, 1970).

As the riots intensified, the angry mob directed their anger towards specific targets. "The workers' ire was directed towards those who, in their eyes, were the cause of their misery: the factory owners and the middlemen who bought the finished products at low prices" (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.).

As noted in the book "The Invention of the Modern World" by Alan Macfarlane, the weavers turned their ire toward Jacquard, and “destroyed his workshop and looms and burned his effigy in the square. Jacquard fled for his life and for some time remained in hiding."

The extent of the damage was significant, as the rioters attacked not only the workshop but also the Jacquard's house, as well as those of other factories and wealthy merchants’ homes in the area.

There are various accounts of Jacquard's escape from the mob. One popular story suggests that Jacquard disguised himself as a National Guardsman in order to slip past the rioters unnoticed. Another account suggests that he was smuggled out of the city in a hay cart, disguised as a farmer.

Regardless of the specifics of his escape, it is clear that Jacquard's life was in danger during the riots. In the aftermath, many of his colleagues and fellow merchants who had supported the introduction of the Jacquard loom were forced to flee Lyon for their own safety.

The National Guard was called upon to restore order and suppress the uprising. The National Guard was a reserve military force made up of civilians who could be called upon in times of emergency to defend the state. In Lyon, the National Guard was composed mainly of bourgeois citizens who were sympathetic to the government and opposed to the working-class canuts.

Initially, the National Guard was successful in suppressing the canut revolt in early November 1831. However, the violence continued to spread and the National Guard found themselves increasingly outnumbered and outmatched by the canuts. The situation eventually escalated to the point where the government had to send in the regular army to restore order.

The army was able to crush the rebellion and reestablish control over Lyon by mid-November, but not without significant bloodshed.

According to one source, "the troops took every opportunity to shoot at anything that moved, smashing windows and doors, destroying everything in their path." This caused many silk workshops to shut down, further damaging the industry.

A painting depicting the second Canut Revolt in 1834. There was one more in in 1848, making a total of three.

After the riots rom a report in the Prefect of Lyon, "the majority of the silk workshops were destroyed or seriously damaged, as well as many homes belonging to the silk manufacturers."

The number of casualties is estimated to be around 600, with many more injured and arrested.

The consequences of the revolt had long-lasting effects on the silk industry in Lyon. Many workers lost their jobs, and the city's reputation as a center for silk production was severely damaged. The destruction of the silk workshops meant many had to completely start over.

Former Canut workshop turned into a modern loft in Lyon.